Common knowledge is that teachers are feedback machines. This is not always true though. There is a major difference between grading and feedback.

Grading is the act of giving a numerical or other score to something. It is frequently based on some criteria, but since that criteria is not always clear, it doesn’t always act as feedback.

Feedback is the act of giving actionable information on something.

I bet you have experienced the difference when you were at school. You get a paper back, it says “B-” on the top, with no extra elaboration. Your friend who wrote a very similar paper, which you know because you proof read each other’s work, sports a “B+”. What did they do that you didn’t? It’s not clear. You have both been graded, but neither of you got feedback, outside of the fact that both were adequate.

Now, you have also played a sport in school or were in a play or band. All of these activities tend to give feedback. Your running coach may have said, “When you run, you tend to hold your breath. Make sure you are always taking breath in through your nose and out of your mouth.” That is to say, they observed you. They noted something that impaired your performance and they explained how to fix it.

Am I giving feedback?

How can you tell if you are grading or giving feedback? A good indication is if your students know what they need to improve, specifically.

If you are grading and not giving feedback they may give you empty student platitudes. Phrases such as “study more” or “try harder” are student speak for “I have no idea”. If they knew what you wanted and it was in their power to give it, they certainly would.

If you are giving feedback they should be able to tell you what skill(s) they are working on. They may say “I need to end sentences with punctuation” or “I need to increase my math fluency”.

How do I give feedback?

I read some research from RJ Marzano on feedback when I started teaching high school in Arizona. I will be borrowing heavily from it here. I suggest reading his book on the matter for more in-depth information.

Feedback needs to be four things: Specific, timely, targeted and actionable.

Specific: It identifies exactly what needs to happen.

Timely: It is given close to the task, ideally when that feedback can improve or change the outcome. This is why the grade on the essay is a very bad excuse for feedback.

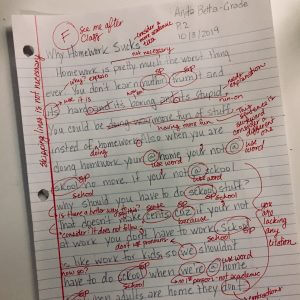

Targeted: The feedback should pertain to a very small part of the task. You may not for instance use something like this:

Actionable: it really ought to be something it is within your student’s ability to change. You can’t say “Timmy will read at grade level” if Timmy is a high schooler reading at second-grade level.

The best way to hit these sweet spots is with rubrics. You can make a rubric for almost anything. The best rubrics have the four sections that follow:

- doesn’t attempt the skill

- attempts the skill but isn’t successful

- does the skill with help

- does the skill without help

These work with any skill you are trying to teach from tennis swings to physics papers. Each one tells you something important.

If a student is not even trying, they have no idea what to do. Very few students will not even attempt a skill for a non-emotional impairment reason. They need one on one help to get to the bottom of what they can’t do and/ or don’t get.

If a student is attempting, they’re willing to give it a try. They kind of understand what you’re asking and they give it a go. They need greater guidance on the skill to improve.

If a student is completing it with help, they just need more practice. You can start to take away any scaffolds you have them using, a little at a time.

If the student can do the skill without help, congratulations! They learned it. You can give them the next task, or use them to help coach those still working on the skill.

I am not suggesting you make a rubric for everything you do! There doesn’t need to be one for every practice. One writing rubric for instance can be used in almost every practice. You can focus on one skill and see where every student falls.

For math, you can create a rubric for how students are approaching a problem and then use it often as well. Are they using any strategies when faced with a difficult problem? That would be a good use for a rubric.

In future posts, we’ll help you streamline your feedback process but some quick ideas are:

- use a white board sleeve to quickly circle where a student is on the rubric

- have students use a rubric for their own performance or that of a peer

- walk the room and give feedback as students work

- have one on one conferences with students about their skills. This works well while everyone else is working alone or in groups.

There are many ways to give feedback, but it is worth it no matter how you do it.

How does feedback impact learning?

When I started teaching I did a ton of grading. I graded everything. I made myself crazy putting a sticker and score on every piece of paper my students produced.

I noticed that my students liked the stickers. They liked when they got good grades, but most of the time, they threw the work out with a shrug.

I didn’t understand this. They worked hard on this stuff and I worked hard assigning it a score, so why the lack of regard?

Well, the item was not useful anymore. Outside of the off chance I forgot to hit save on my grading program, there was no reason to keep it.

Feedback changed this dynamic immensely. I no longer “graded” anything except those final, finished products.

This took a ton of pressure off my students. They were not worried about handing in a piece of work. I had already seen it many times and gave them feedback on it. They knew what score they would be getting. I didn’t have to tell them. They held onto the work to use as a model in the future or because they were proud of it.

The feedback along the way helped them feel they would be successful. They were not always happy to be told they needed to do more, but it didn’t leave them confused.

It was empowering for them, it gave me less to grade and gave me much better work. If something wasn’t done, I didn’t just enter a zero and shrug. I would give the partially done work back to them, and ask it be finished correctly. It kept them on the hook for the work, and by extension the learning. Students learned much more from this trial and error approach. My scores were much higher on tests for my students when I adopted this approach.

Kids were learning and I got a weekend. It was a win-win.

What do I grade?

Well, not much. I was a big fan of check-in progress scores, or what could be called “performance grades”.

Outside of these, the only grades I gave were on finished products and tests. If I assigned a project or an essay, I only graded after I had given it feedback on many occasions. The student turned it in almost as an afterthought.

A test was also usually graded, but I also preferred a “revisions” approach on this. A test is meaningless if a student can’t learn from it. If they can use the feedback to make a change and then do, then it is a useful exercise for them and not just for me.

Grades are a poor motivation for students. It will usually only prompt them to do enough to not fail or be bothered by their family. A few high achievers will care, but grades don’t build intrinsic motivation. They don’t build confidence in a meaningful way.

Use them thoughtfully to help students to grow in their skills. Give feedback first. You will find that your classroom runs better and your students learn more.

Who could say no to that?

2 comments

SMiller

Completely agree! Grades are dubious, subjective and relative to the other writers in the class. . . unless a rubric is used. I still need reminders to target my feedback, so I appreciate the post. STTA will help.

Katrina Glenn

Concurred. It’s always great to be working to improve and target our feedback to be even more individualized and encouraging 🙂 So glad that this lovely blog has helped!